Ridley Scott's Lost Dune: Unveiling a 40-Year-Old Script

This week marks four decades since David Lynch's Dune premiered, a box office flop that's since cultivated a devoted cult following. Its stark contrast to Denis Villeneuve's recent adaptations highlights the enduring fascination with Frank Herbert's epic novel. This article delves into a previously unknown chapter of Dune history: Ridley Scott's abandoned version.

Thanks to T.D. Nguyen's discovery within the Coleman Luck archives, a 133-page October 1980 draft of Scott's Dune, penned by Rudy Wurlitzer, has surfaced. This script, a significant departure from Frank Herbert's original screenplay, offers a unique perspective on the story.

Scott, fresh from the success of Alien, inherited a screenplay that was both faithful and cinematically unwieldy. He selected a handful of scenes but ultimately commissioned Wurlitzer for a complete rewrite. This version, like Herbert's and Villeneuve's, was envisioned as the first part of a two-film saga.

Wurlitzer described the project as incredibly challenging, stating that structuring the narrative consumed more time than writing the final script. He aimed to capture the book's essence while infusing it with a distinct sensibility. Scott himself later confirmed the script's quality.

Several factors contributed to the project's demise: the death of Scott's brother, his reluctance to film in Mexico (as per De Laurentiis' demands), budgetary concerns exceeding $50 million, and the allure of the Blade Runner project. However, a key factor, as revealed in A Masterpiece in Disarray – David Lynch's Dune, was the script's lack of universal acclaim within Universal Pictures.

This article presents a detailed analysis of Wurlitzer's script, allowing readers to assess its cinematic merits and potential for commercial success. While Wurlitzer and Scott declined to comment, the script itself speaks volumes.

A Reimagined Paul Atreides

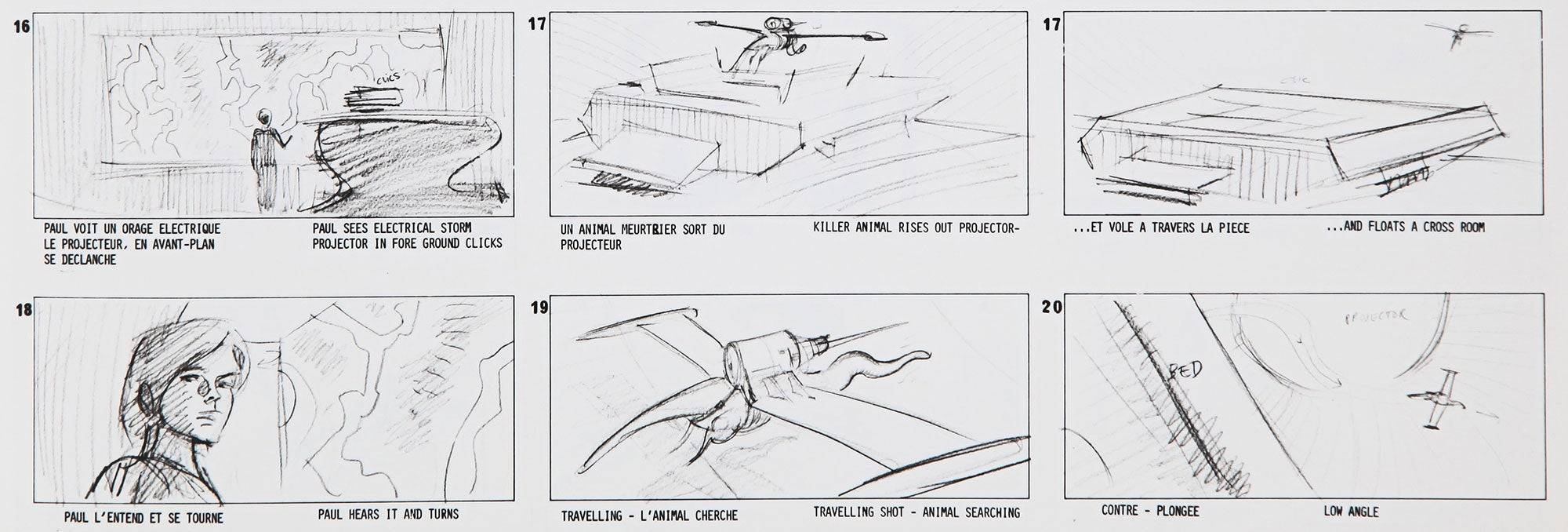

The script opens with a dream sequence depicting apocalyptic armies, foreshadowing Paul's destiny. Scott's signature visual density is evident in descriptions like "birds and insects become a whirling hysteria of motion." The 7-year-old Paul, far from Timothée Chalamet's portrayal, undergoes a trial by pain, his Litany Against Fear intercut with Jessica's, showcasing their psychic bond. The burning hand imagery echoes Lynch's version, albeit non-literal.

This Paul displays a "savage innocence," demonstrating assertiveness and quickly surpassing Duncan Idaho in swordsmanship. Producer Stephen Scarlata notes the difference between this assertive Paul and Lynch's more vulnerable portrayal, highlighting the contrasting impact on audience engagement.

The Emperor's Demise and Political Intrigue

The script introduces a pivotal twist: the Emperor's death, a catalyst absent from the novel. The Emperor's funeral, a mystical spectacle, leads to the transfer of Arrakis to Duke Leto. Baron Harkonnen's subsequent attempt to negotiate spice production highlights the power struggle at the heart of the story. A key line, nearly identical to a famous line in Lynch's film, emphasizes the spice's significance: "Who controls Dune controls the Spice, and who controls the Spice controls the Universe."

The Guild Navigator and Arrakis

The script depicts the Guild Navigator, a spice-mutated creature, as a humanoid figure floating in a transparent container, foreshadowing elements of Scott's Prometheus. The family's arrival on Arrakis showcases a medieval aesthetic, contrasting with the technological elements of the novel. Liet Kynes' introduction of Chani highlights the ecological consequences of spice harvesting. Their ornithopter flight, interrupted by a sandworm attack, mirrors the hellish cityscapes of Blade Runner.

Arakeen is portrayed as a squalid city with stark class disparities, inspired by The Battle of Algiers. A new bar fight scene, reminiscent of 1980s action films, introduces Stilgar, who swiftly executes a Harkonnen agent. The scene with Jessica receiving a crysknife and witnessing the suffering of the populace emphasizes social inequality.

The Deep Desert and Confrontation

Paul and Jessica's desert escape is intense, featuring a crash landing and a perilous journey. The encounter with the sandworm mirrors Villeneuve's adaptation. The script notably omits the mother-son incestuous relationship present in earlier drafts. However, a scene of Paul and Jessica lying together on a sand dune retains a hint of the original provocative element.

Their refuge in a giant worm carcass leads to an encounter with Fremen warriors. Paul's duel with Jamis, similar to Lynch's film but with a more brutal depiction, solidifies his role as the Lisan al-gaib. The Fremen ceremony and Paul's acceptance into the tribe mirror elements of Dune: Part Two. Chani's acceptance of Paul, despite her grief, underscores the shifting dynamics.

The Water of Life ceremony, a surreal and mystical sequence, features a shamanistic figure and a giant sandworm. Jessica's transformation into the new Reverend Mother and the Fremen's acceptance of Paul as their Messiah conclude the script, setting the stage for a potential sequel. The script notably omits Paul's sandworm ride, a key element Herbert hoped to see in Scott's film.

Conclusion

Scott and Wurlitzer's Dune offers a unique interpretation, emphasizing ecological concerns and political intrigue. The script's grimdark tone and deviations from the source material likely contributed to its rejection. The script's strengths lie in its visual storytelling and the exploration of ecological and political themes, aspects that are less prominent in other adaptations. The script's legacy includes H.R. Giger's sandworm design and its influence on later projects. While never realized, this lost Dune provides a fascinating glimpse into an alternate cinematic universe. The themes of environmental decay, fascism, and the awakening of the oppressed remain profoundly relevant, ensuring the enduring appeal of Herbert's work.